Nature: Interview the Actor & Director

14th October 2025

When I sat down to write about Nature, I found myself struggling to summarise it. It is a piece that is both epic in its themes and yet deeply personal, exploring topics like mental health, our relationship to nature, witnessing global atrocities, the tension of dual identities, and the struggle to self-express, all packed into a single, spiralling shot. It casts a broad thematic net, but this dramatic monologue – one in a series by Àkàndá – still cuts to the core of these issues with brutal honesty and palpable emotion, brought to life by Mitesh Rajput in his magnetic performance. As Mitesh’s character says, ‘construction is deconstruction’, and this film aims to unpack the layers of these topics and the individual, painting a vivid psychological picture of a man enduring to put words to the world.

I wanted to start by asking Daniel and Mitesh about the beginning of this project which, with a film rooted in spirals, is at the center. It was during the pandemic, a time where we were all unfathomably stagnant in the midst of turmoil: ‘we were all kind of going through something as a collective experience as humans – not any particular country but globally,’ said Mitesh.

The consequent idea of spinning camera work was embedded in this project from the beginning: Daniel came up with this formal concept following his creation of another dramatic monologue titled Seema (2020). In this film, its title character speaks about contending with a history of self harm while trying to move forward and give new life. Constrastingly, Nature is about articulation, following a character grappling with the weight of the modern world and struggling to express it. When comparing the two, Daniel stated, ‘In [Seema], the camera zooms outwards so you see her in increasing isolation as she speaks, whereas with [Nature] I wanted to try having the camera spiral around the character to show the instability of his mind.’

This simple yet powerful idea was the springboard for the project, leading Daniel to work with co-writer Justin John Hills until they were ready to cast the film. Daniel and Mitesh already knew each other through mutual friends, but it was a Facebook post that brought them together in the audition room. Daniel said, ‘I told Mitesh “I want to work with you, it just makes it easier that your audition was the best one we got”’ and the two began their partnership from there, not just as director and actor, but as collaborators and artists.

Mitesh commented on his excitement at joining the project, having just experienced the deep disappointment of a Covid graduation from drama school: ‘The last six to seven months in my training were interrupted by covid. I came into the industry at a really challenging time where there was no work […] everything was falling apart.’ Being from a theatrical background, this was his first professional gig, as well as his first time on camera. His enthusiasm to jump right into something new- and to masterfully adapt as he went- leaps out in his performance which is equal parts gritty, playful, and heartfelt.

Getting Comfortable with Discomfort

It strikes me that the development and filming of this project was an equaliser, flattening the typical hierarchies between director and cast into an exciting, collaborative creative landscape. Mitesh talked about how being given artistic freedom helped him settle in and enjoy the process of navigating so many firsts at once: ‘I loved that it wasn’t just me being an actor but it was also this really good process in terms of me as an artist. Daniel wasn’t telling me, “oh you just do what I tell you because you’re an actor,” it wasn’t like that. It was truly a collaborative process where I had a lot of input and so did he.’ His theatrical training also deeply suited the one-shot nature of the film, ‘“[Daniel] told me to do what you would do in a theatre, which was a good advantage for me to get comfortable – once that motor is on, I’m on it, off we go, there’s no cut.”’

The small-scale production and an encouraging crew atmosphere also enabled Mitesh to flourish on-screen, despite feeling incredibly nervous to start. Although he admitted that he is still uncomfortable with cameras, he discovered their power on this set: ‘The camera is there for you. It captures everything, you don’t really have to do much – you can just be.’ It was in learning this that he came to thrive during the filming process and this curated confidence shines through in his embodiment of Meer.

I found Mitesh’s honesty about his discomfort at the start deeply inspiring; it dosed me with a little more courage to take on new and challenging projects, and I hope that, in sharing it, this bravery can encourage other young creatives. He expressed that, like most artists, he grappled with a lot of self-doubt about the gaps in his training when approaching film, but it was his self-awareness and willingness to bridge that gap that became his sharpest tools: ‘I kept telling Daniel, “this isn’t my area, please tell me what to do, please guide me through all of this.” He told me, “this is exactly why you’re right for this part.”’

The Writing Process

One of the most exciting parts about Nature is the dynamism of its script. The monologue twists, stumbles, pauses, and bites. It is made up of ongoing articulation and re-articulation that is both dizzying and painfully relatable to anyone trying to put words to what is wrong with the world. Daniel and Mitesh revealed to me that the script was developed with this same continual motion and adaptation: ‘It was a constant back and forth between hearing how Mitesh performs and editing the script,’ said Daniel. Mitesh expanded, ‘Every time we got together to rehearse there was a new discovery […] We were always peeling the layers – like an onion- really getting to the bottom of the essence of what is actually going on with me.’

Motion is the thematic and formal beating heart of this film, and the monologue’s meandering structure was crucial from its conception. When I asked how they managed to keep the script focused despite its sheer breadth of themes, Daniel revealed that the springboard, above all the rest, was this idea of the struggling mind: ‘There wasn’t one specific situation or theme that was the main anchor, but the fact that we are currently constantly in a state of chaos and turmoil, and asking the question “how do you stay calm and stay at peace when the world is literally burning?” – and there’s not one reason why the world is burning.’

I commented that I would struggle to know where to begin with writing about such an ambitious concept, and he emphasised that it is this very struggle for articulation that is core to the project:, ‘When you see how the world is and how you feel in it- because they’re all connected in some way- it’s hard to articulate it. […] Maybe it would have been interesting to have an eloquent person say that in a really coherent way but that’s not everyone. Sometimes the most truthful things are hard to articulate.’

Mitesh also commented on how human nature was a large inspiration for the writing and performance: ‘My impulses as a human were very helpful […] we do that as humans, we talk about everything, every little thing, and we bounce between them.’ It appeared, then, that rather than trying to avoid rambling, Daniel and Mitesh leaned into it. What results is a script whose very form acts as a powerful commentary on human nature and the beauty of ineloquence.

A Bilingual Script

Besides this being his first time on-screen, this was also Mitesh’s first writing credit, which arose with the introduction of his native language, Gujarati, into the script. This helped Mitesh feel comfortable and took his performance to a different place: ‘When I speak Gujarati, to this day, it brings out a behaviour that is quite raw […] Sometimes what I need to do if I can’t get into it, is take the script, translate it into my language, and see what behaviour comes out of me.’ Their writing method then became a constant investigation into where this behaviour was needed: ‘There were some bits where I would feel stuck or couldn’t find the motivation or what the ‘pinch’ was for my character so he could come out. I found they would get lost in English; so what we started asking was “how would you say it in Gujarati?”.

Both artists framed native languages as holding an expressive and creative magic that cannot be cast in second or third languages. The raw transcendence this brought out in Mitesh’s performance is one I found deeply resonant; I myself cannot understand Gujarati, and yet I felt Meer’s meaning in every syllable.

Daniel equally also drew inspiration from multilingual people in his life and in Bollywood and Nollywood: ‘I’m not bilingual unfortunately, but I’m around a lot of bilingual people, including my parents. One thing you notice about people who speak multiple languages is there is always a subconscious default for getting into a deeper emotional state […] Most of the time this tends to be the non-English language.’ He did emphasise that English was still important to the film, as it offers a different kind of authenticity, and Mitesh is still magnetic as ever in his third language. Excavating both language’s emotive powers and creating a balance was something they had to navigate carefully. ‘This isn’t to say we pressed the Gujarati button every time, but we intended to do it in a way that allowed the language to flow and emphasise that this is the language of rawness,’ said Daniel.

Authenticity

The topic of rawness is one I find particularly interesting about Nature. It’s there in the organic implications of the title, but its form, the dramatic monologue, is inherently about what is revealed to– but more importantly what is kept from– the audience. The film’s opening lines proclaim: ‘Performers. We are all some type of performer. We all act.’ This gesture to acting created a wonderful irony, given the film’s emphasis on rawness; Meer has outbursts, but is equally aware he is being watched and circled by the viewer. I found myself asking, ‘Is he acting still?’ and jumped at the opportunity to direct this question to the film’s creators.

Mitesh’s answer emphasised the vulnerability of his character in this moment: ‘I agree that we do act a lot in everyday life without realising. We have so many masks on: the jewellery and the language. The way I do my hair is a mask, the way I do my beard is a mask […] But, as a character, I don’t think he’s acting.’ He expanded: ‘He is really raw right now […] We didn’t intend for audiences to perceive a performance within the performance.’ Here, the Gujarati plays a crucial role, signposting emotional, and emotive expressions that are uncalculated and honest.

Daniel’s response was similar: ‘I also don’t think he was acting […] He was tired of wearing the mask, even if the act of removing the mask is an act. It is a performance, but acting doesn’t mean it’s inauthentic.’ When I rewatched the film, I realised that these moments of direct address to the audience create an unexpected kind of transparency – in addressing us, he is addressing the knowledge that he is being watched, which is staggeringly honest. I think one of the greatest strengths of Nature is how it highlights that performance doesn’t equate dishonesty, rather, it is simply a part of being human. As Daniel stated, quite aptly: ‘Whatever comes out is exactly what he thinks. He’s removed his mask to perform his true self.’

The Power of Nature

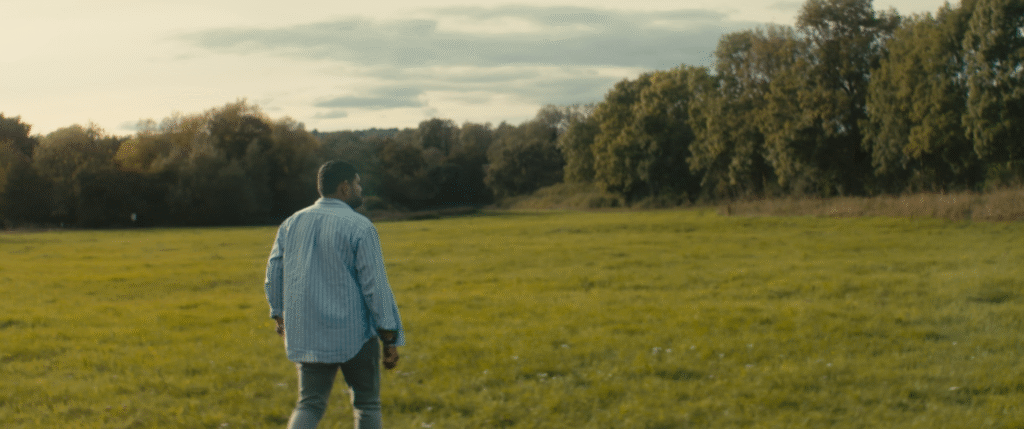

One of the film’s centrifugal themes is the frustration with not being able to feel at peace despite being surrounded by nature, despite the knowledge that connection to nature is crucial for honest self-expression. It’s only once in this natural environment – a starkly British field, bathed in golden hour light- that Meer feels he can truly shuck off the mask and be himself. This ongoing tension between nature’s capabilities and our estrangement from them is one we all have to navigate, and Meer’s journey gives us a grounding hope.

Daniel explained that the external pressures of modern society are the reason Meer is so incapable of feeling satisfied with the beauty around him: ‘We are removed from nature, and when we try to return to it it can feel like a foreign place that’s home.’ This alienation is also one of the many reasons we are so able to ravage our environment: ‘we are part of it, and the more we disassociate from it, the more inhuman and destructive we become […] We have to know that we are a part of nature because that’s where our humanity comes from.’

Once we are able, the film frames reuniting oneself with the natural world as a salve for suffering. This is a philosophy shared by Mitesh: ‘Every time you see greenery, your eyes just automatically relax into your head. Every time I hear an ocean I breathe, it changes my instrument, my biology.’ In this sense, nature is also transformative. Mitesh told me how crucial it is for his craft as an actor, not only in finding one’s true self, but also in modifying it: ‘Art, artists, and nature go hand in hand – we use nature as a tool. For example, we do elements as one way into a character: earth, water, space, and fire. In movement class, we embody animals and see what behaviours it can bring out of you.’

The way Nature’s creators emphasised the safety and the ineffability of nature was reminiscent to me of how they spoke about one’s native language. Both are talked about as refuges that can’t quite be replaced or summarised by those that inhabit them, and this binding magic is portrayed beautifully in the film. The visuals are simple, yet overflow with both aesthetic and thematic beauty, and I found the use of such an open space as the project’s sole location to feel both incredibly exposing and freeing.

Direction

When I asked about how Nature was shot, I was deeply impressed at the precision in both planning, filming, and editing that it required. Daniel said, ‘It wasn’t all choreographed to a T, but what I wanted was for Mitesh not to constantly follow the camera.’ This was a directorial decision I loved, allowing us to literally see all sides of Meer, not just linguistically, but physically: ‘At first we had him constantly turning to face the spiral, but then we started playing with him delaying his turns, allowing us to see his back.’ This decision also amplifies the trust built between audience and character: ‘There were times when he was speaking and the camera was turned, and you get him to say “are you hearing me?”, which allows for a more interesting audience interaction,’ Daniel said.

One-shots are notoriously difficult to execute, and this was no exception. Given the camera’s constant movement around Mitesh, the crew were also required to remain in constant motion, ensuring that every detail was right, down to making sure their shadows weren’t in frame. ‘Anand was orbiting Mitesh and I was behind him the whole time, like a conscience, whispering to him to go closer or draw back,’ Daniel said. The footage then also underwent meticulous editing by Daniel, who manually stabilised large sections of the film given software wasn’t cutting it: ‘You could feel the steps in the camera movements which I had to stabilise painstakingly in post- I lost my mind.’ His devotion to detail really shines in the final viewing experience and left me wholly immersed on my first watch.

Collaboration

It’s clear that the success of this film is rooted in authentic, active partnership, and Daniel and Mitesh’s approaches allowed them to work together really cohesively. Trust, committed communication, and remaining open were the stand-out features of their professional relationship that made Nature so resonant.

Mitesh told me: ‘I know Daniel is a really experienced filmmaker and I trusted him. That was one of the biggest elements – trust is everything […] Otherwise it’s not going anywhere.’ Ongoing communication was also fundamental: ‘We would just text each other and keep communicating. These are really simple tools but they are so important, because I could be drumming one roll in another rhythm and my collaborator could be drumming a completely different roll in a completely different rhythm and then we can never meet.’ This also helped keep their shared passion for the film alive; the two were continually uplifting each other:‘On days where I was feeling my energy go down, Daniel would pick it up, and vice versa […] It’s so easy with these types of projects for the energy to die out, we were both very good at keeping the momentum going.’

Being open and honest was also a core part of this collaboration – just as Meer gives us his raw thoughts, Daniel and Mitesh were always honest with each other: ‘We would share raw thoughts and ideas, even if we didn’t know what the idea was really about […] I would just throw it out, Mitesh would catch it,’ Daniel said. He described that this is when he most enjoys his work, and I recall him having a similarly playful, collaborative relationship with Atticus Orsborn on The Three Little (Proletariat) Pigs (2023).

Despite this being a pattern in Daniel’s creative approach, he emphasised how rare it can be to be able to work with someone so open to that kind of back and forth: ‘It makes me grateful that we got to do this; it’s not common – not every actor would be able to have that approach.’ Collaboration is something he describes as crucial to high-quality storytelling, explaining that, ‘My idea for the character will only have one dimension […] Everything that Mitesh brought I couldn’t have brought, and I wouldn’t have even thought about bringing it.’ It’s going beyond just inclusion, but celebration of alternative perspectives that Àkàndá champions, and we see its creative potential embodied beautifully in the creative partnership between director and actor in this film.

Staying Committed to Art

Beyond continually pushing and empowering one another, I asked about the other ways in which Daniel and Mitesh keep themselves committed wholeheartedly to their crafts. In a social climate that increasingly devalues the arts and filmmaking, how can we continue creating?

Daniel’s answer was simple: ‘If we don’t, then who?’ He emphasised art as a necessary tool for survival: ‘Now more than ever we need more perspectives and creative ideas to come out. […] because we are currently in a world where people aren’t as easily attentive to the expressions or perspectives of people that they don’t immediately relate with, I think art is one of the best ways to convey those things, more so than any other medium.’

The power of art to reflect and enact change is core to Àkàndá ’s mission as an organisation: ‘It’s kind of cliche to say that art will save the world, but without art the world is dead […] it opens a dialogue, it allows people to understand.’ The deep emotional resonance I experience watching Nature, despite my stark differences from Meer, is a testament to art’s transportive qualities, that can unite people in the same stroke with which it paints our differences.

Daniel declared, ‘Regardless of the situation, even if no one is going to support, I would still find a way, as I have done with some of the films I’ve made so far,’ and this is evident in many of the volunteer or zero-budget projects he’s helped create. Art-making is truly a labour of love for him.

Mitesh feels similarly, emphasising how the ‘why’ is the most important thing to remind oneself of as an artist: ‘If that “why” doesn’t make you black and blue in your face then you’re not going to pick up that pen, you’re not going to write that script, or you’re not gonna create anything.’ He also agreed on art being indiscernible from life: ‘I really cannot imagine a life or world without art […] It’s inspiring, it’s breathing life. When you breathe in, that inhale itself means to inspire if you trace back the etymology.’

A Call to Action

At the same time, both creators pointed to a need for increased resources for artists. As much as creatives need a core passion and drive, they also are deserving of external support to help them continue creating. Daniel said: ‘It’s structured so that artists are doing less making, and more of trying to negotiate why their project is viable.’ He expanded, ‘It’s not even about asking for those opportunities, it’s about creating that space ourselves. No one is going to give us that, we either have to take it or create our own table.’ Àkàndá is an example of one such table that seeks to open up and redefine the mainstream arts. Mitesh emphasised that this wasn’t to complain, but to platform those who aren’t even given a foot in the door: ‘I personally feel I am far more privileged than my people in India because I am at one of the prestigious drama schools in NYC, because I lived in London, I have opportunities […] It’s good right now, but we could do better.’

Daniel also compared the current mainstream to feedback loops seen in AI, a topic that is looming and pertinent to many artists: ‘When you have software that produces an image and you ask it to reiterate the same image, over time it begins to morph into something unrecognisable. The only way to do something new, you have to input new information.’ He said, ‘In a world that is needing new ideas, the structure doesn’t allow for that. It benefits from the status quo even though the status quo is crumbling.’ In the face of this, he remains headstrong in his vision for his artistry and his production house: ‘Even if that system is going to crumble, let us do what we can to keep generating new ideas. If we don’t say anything, then we will just fall apart with it.’

Closing Remarks

Though meandering and brimming dizzyingly with themes, Nature still left a specific and memorable imprint on me upon my first watch. The conversational, disorganised nature of the speech made it feel truly authentic, like I too was safe to slip off my mask and immerse myself in the film. I thoroughly look forward to others being able to access that same feeling when they view it.

When I asked how they would describe the project in three words, these are what they said:

Daniel (Writer, Director, Editor) said: ‘Authentic. Raw. Truth.’

Mitesh (Writer and Cast) -much like his character- struggled to compress so much into so little, so I allowed a sneaky fourth word: ‘Truthful. Fun. Beautiful Journey.’

Àkàndá invites watchers or fellow artists to also partake in this beautiful journey with the film’s creators. I am positive you will gain something deeply meaningful from watching Nature – and, at the very least, you’ll bear witness to the cinematic beauty that results from passion, vision, and true collaboration.